We stumbled across a story on This American Life that looked into this question. Traditionally, it is thought that people stay poor because of bad education, a lack of resources, and a negative environment. But new research has identified a stronger predictor of poverty: stress.

Growing up in an adverse environment physically changes a developing child’s brain, and this makes it difficult to learn, socialize, and deal with setbacks. The effects of the stress caused by a difficult home life are huge, and they extend way beyond childhood to life as teen and adult. There is, however, a way to address this: a secure attachment with an empathetic parent can protect kids from the stress of an adverse childhood.

Kids growing up in poor households are exposed to many more stresses than their peers from better-off homes. Researchers call the following stresses “Adverse Childhood Experiences” or ACE.

The ACE Study is a major American study that looks at how these childhood experiences affect adults decades later. The study has found that as a person's ACE score (their number of adverse childhood experiences) increases, so does their likelihood of significant emotional, behavioral, and physical health problems.

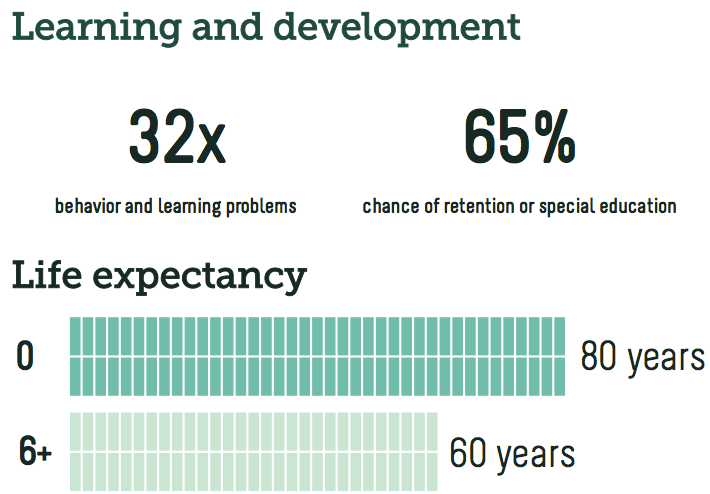

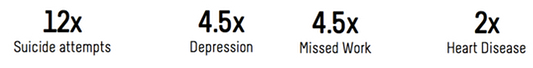

Kids who have had four or more stressful experiences are 32 times more likely to have behavior and learning problems (TAL). They live shorter lives, and have significant health problems. If you have four or more difficult childhood experiences, you are “two and a half times as likely to develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adulthood, twice as likely to have heart disease, two and a half times as likely to have hepatitis, four and a half times as likely to be depressed, 12 times as likely to attempt suicide,” says Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician who works with kids living in poverty.

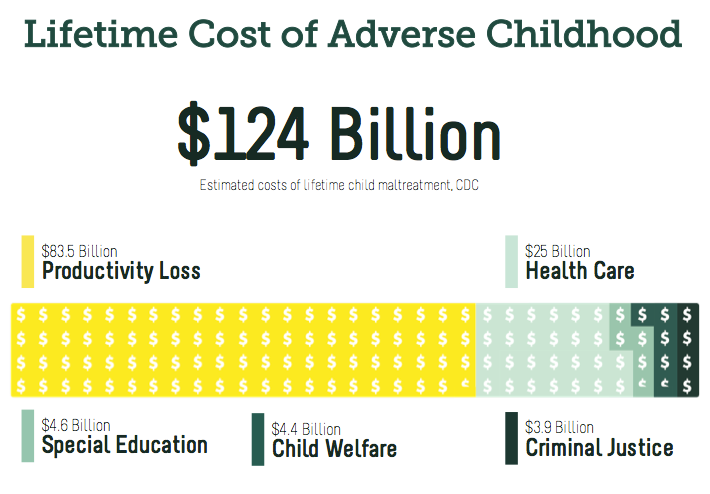

There are also significant monetary costs to adverse childhood experiences. The CDC estimates that the lifetime cost of child maltreatment for cases in one year is approximately $124 billion. This is due to lost wages, health care costs, welfare, incarceration, and other costs.

The Development of the Person: The Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaptation from Birth to Adulthood

A mother rat licks her pups

What is it about these experiences that leads to such troubling outcomes? When you are stressed, your body activates it’s fight or flight response. It releases adrenalin and cortisol, hormones which dilate your pupils and increase your heart rate. They shut off the parts of your brain that control executive function and cognition, and activate the parts that initiate aggression.

This would be helpful if you had just encountered a bear in the woods. “The problem is when that bear comes home from the bar every night,” says Nadine Burke Harris. “And for a lot of these kids, what happens is that this system... [is] activated over and over and over again.” When this process repeats, you brain starts to ingrain these pathways deeper and deeper.

In the brains of kids growing up in stressful homes, this aggressive state becomes normal, and the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that governs self-control, memory, and reasoning, doesn’t develop normally.

Childhood stress is very common in low-income households, and it can have huge impacts on kids' whole lives. There is hope, however—if kids have a secure attachment to an empathetic parent, the negative effects of an adverse childhood are erased.

Starting in the 1970s, researchers at the University of Minnesota have been studying a large group of children before their birth through adulthood. They have found that the kids that had a secure attachment with their parents were protected from the stress of their adverse childhood. They were more socially confident and competent, more likely to graduate from high school, and better at dealing with setbacks than their peers who didn't have a secure parental attachment.

A study was performed on rats where researchers stressed infant rat pups by picking them up from their homes, and then putting them back. Most mothers licked their pups and comforted them—but some didn't. The rats who were comforted by their mother were healthier, more curious, and performed better in mazes. When the coddled rats then had pups of their own, they also were comforting mothers, unlike the uncoddled rats. When neroscientists looked at their DNA, they found that some genes in the uncoddled rats had actually been switched off—the way they were treated as pups actually changed their DNA!